Endrew, a child with autism, became the center of a landmark Supreme Court case that rejected the "merely more than de minimis" standard applied by his school and set a higher standard for meeting requirements under FAPE and IDEA legislation.

First, some context.

In April 2010, Endrew's parents rejected his 5th grade Individualized Education Program (IEP) proposed by Douglas County School District. The parents, after seeing that the IEP was materially the same as previous plans under which Endrew's progress stalled, withdrew Endrew from his school and placed him in a private school focused on educated students with autism.

During the course of the academic year at the new private school, Endrew "thrived". His behavior improved drastically and he progressed toward most of his academic goals.

Endrew's parents sought reimbursement for the cost of private education, which we know was substantial. Although they faced defeat in the initial review and appellate courts, they eventually took the case to the Supreme Court, arguing that his school failed to meet it's duty to provide free appropriate public education (FAPE) as defined by the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

Got it. So, is there a defined standard?

Good question! It's a challenging thing to answer and is likely the reason the court took this case. During the last major review of the substantive standard (see Board of Education of Hendrick-Hudson Central School District v. Rowley), the Court failed to provide a unifying test for educators and parents to determine if a school was meeting it's "de minimus" standard. In other words, although the Court emphasized that a student would have been given FAPE if their IEP goal was "reasonably calculated to enable the child to achieve educational benefits", the ruling resulted in a wide and varying degree of application for "reasonable calculated" IEP goals.

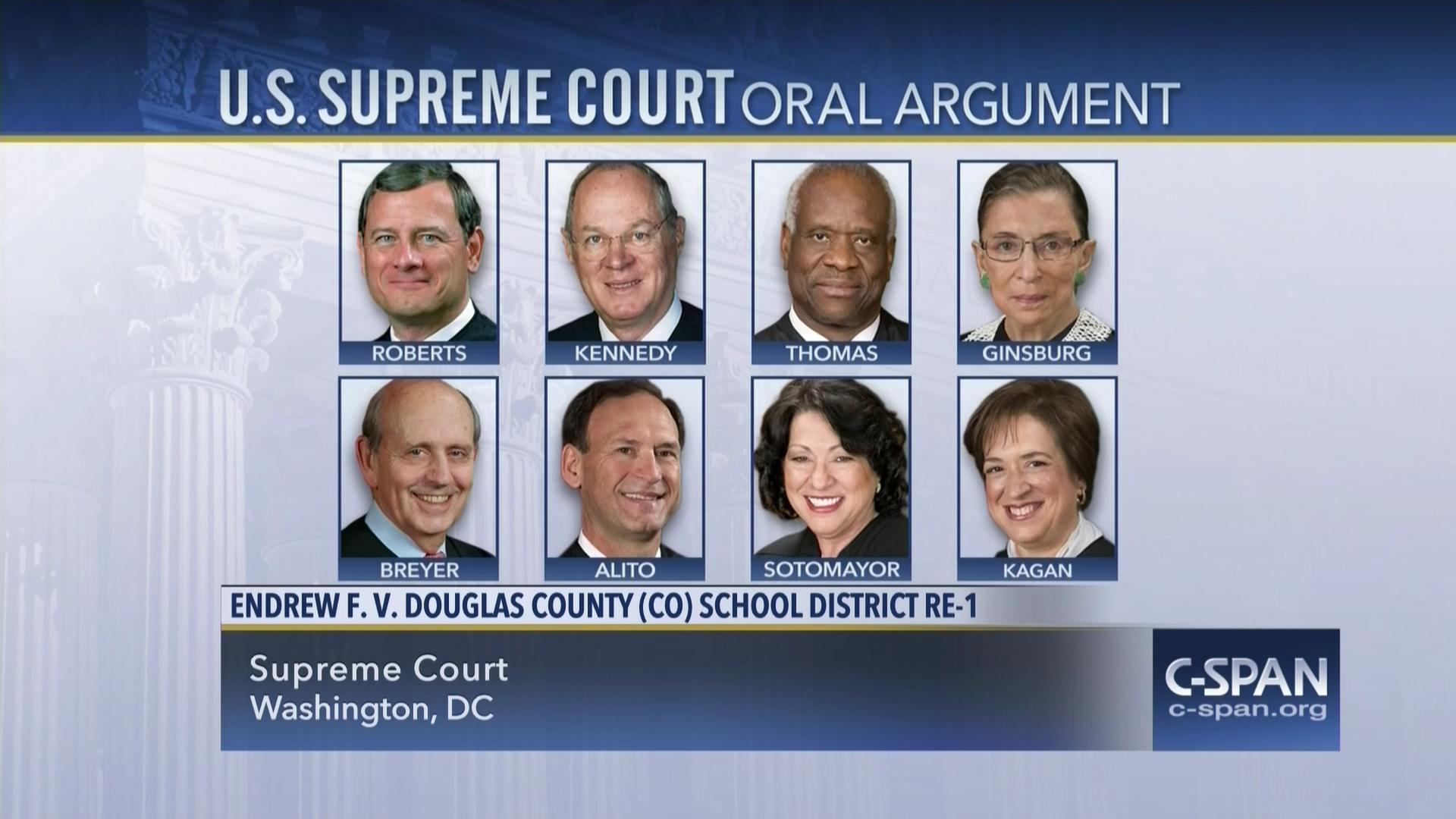

Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District became a landmark case because it clarified that "merely more than de minimus" - literally meaning slightly more than the minimum or "trivial" - was not a significant enough standard within the context of FAPE and IDEA legislation.

According to the new ruling, "every child should have the chance to meet challenging objectives" and it's a district's and school's responsibility under IDEA “to offer an IEP reasonably calculated to enable a child to make progress appropriate in light of the child’s circumstances.”

Importantly, this case focused on autism education, but the new standard applies to all special education students and must be applied to the specific facts of that student.

Challenging objectives? Reasonably calculated? Appropriate light? These sound like more vague phrases.

You aren't wrong. As with most Supreme Court cases, especially in topics surrounding evolving research, therapy, outcomes, and new thinking, rulings can make us wonder, "What next?"

Without getting too technical in an effort to explore the "Now What?", think of this ruling as a call to action. Like most call to actions, we care less about the directions or path and more about a specific outcome.

In the case of special education, the outcomes must (as they should) focus on educational improvement, specifically "challenging objectives". These objectives should align to State academic content standards ("general education curriculum") and must "aim to enable the child to make progress", understanding the "grade to grade" might not be the measure of success.

There are many, many ways to achieve that outcome and educators should consider the multitude of variables (appropriate light) and resulting impact or influence it has on a students educational progress. This analysis is the reasonable calculation.

Of note, IEP Teams are now required to review IEP goals at least once per year, taking into account the initial calculations, appropriate light, and current progress. If circumstances dictate, educators must revise the plan if the student is not meeting the defined goals of the plan.

If you are interested in seeing how the court defined and explained their thinking, see the link below this blog to read the ruling.

What should we be doing differently?

At the end of the day, being an advocate and support system for your students as they progress academically is the standard we should care most about. Technical definitions take the human out of schooling and reduce our students to numbers on a page or a data point to review.

Yet, there are a few things educators and IEP teams can do to ensure compliance with the new Endrew standard. I quote the Q&A documentation below:

IEP Teams must implement policies, procedures, and practices relating to

- identifying present levels of academic achievement and functional performance;

- the setting of measurable annual goals, including academic and functional goals;

- how a child’s progress toward meeting annual goals will be measured and reported, so that the Endrew F. standard is met for each individual child with a disability.

Anything else?

There is always more to the story.

For the purposes of this blog, consider a few things.

First, Endrew's former school (the defendant) became a RoboKind customer after this case, implementing the robots4autism® program in order to meet the higher educational standard.

Second, This ruling does not effect parents' due process rights. As mandated by FAPE and IDEA legislation, parents may take necessary actions to ensure their child is receiving fare appropriate public education in the least restrictive environment conducive to academic growth. If during due process the court or hearing officer determines a school failed to make FAPE available, the family can recoup incurred costs of private placement.

This - not to mention the legal costs that accompany due process - can be an unforeseen and tangible burden on schools and districts. While we vehemently believe in student and parent rights, we also recognize that most educators make meaningful efforts to see their students succeed. Unfortunately, those educators didn't have the tools, training, or support they needed to meet the Endrew standard.

Third, and finally, technology can be a solution. Investing in the tools and resources that help educators support their students is the most straightforward way to show parents (and courts) that you are meeting the Endrew standard.

As always, thanks for taking a few minutes to read this insight brought to you by the RoboKind team! Don't forget to comment / like / share!

P.S. - In case you want to read the details of the case here are a few resources: